|

| The mighty trunk of our Sabal palmetto |

Our most impressive member of the genus Sabal is the Sabal palmetto, which we covered on this blog a few months ago. Indigenous to coastal Florida, Georgia and South Carolina, as well as the Caribbean basin, where the sea protects it from dangerously cold winter weather, Sabal palmetto is now cultivated as an ornamental palm tree throughout the warmer regions of the United States. It's therefore not out of place in the Aboretum, although it isn't native to Louisiana.

But what about the little palmettos? Long-term residents of the Deep South who have ventured into the wilderness will be familiar with our small native palms. These are Sabal minor, the dwarf palmettos. The author first noticed these as a near monoculture in a rural Webster parish field, where acres of muddy ground were entirely filled with two-to-three foot tall specimens of Sabal minor. This palm is not restricted to Louisiana, but can be found across the southern half of our Humid Subtropics.

In 1988, Dr. Ed Leuck collected two Sabal seedlings from the Caroline Dormon Nature Preserve and planted them in the Arboretum. In the catalog and on their labels, he chose to identify them as Sabal louisiana. During the course of basic reading on the Sabal species in the Arboretum, a question arises: What is Sabal louisiana? Is this a deprecated synonym of Sabal minor? A subspecies? A misapprehension? A local name? On this blog, we have previously referred to some specimens as "Sabal minor, the Louisiana palmetto." This reflects the confusion on the issue that can only be cleared up through scrutiny of the historical record.

The story begins with William Darby, a Pennsylvanian who emigrated to Louisiana and worked as a farmer and land surveyor. In his 1816 A geographical description of the state of Louisiana, he wrote:

We have given to this vegetable the name of chamaerops louisiana in the text; and are of opinion that there is a specific difference between the chamaerops palmetto hitherto known to botanists, and that of Louisiana. The chamaerops serrulata of Muhlenberg is certainly not the same with the palmetto of Louisiana; the latter bears a much greater resemblance to the cabbage tree, though much more humble in elevation, than to the saw-leaved palmetto of Georgia.

In later years these unusual plants were noticed by others, including Arthur Schott, who wrote about them in 1857. In 1925, circumstances changed through the investigations of a most highly qualified professional; John K. Small, the curator of the New York Botanical Garden and a botanist specializing in the vegetation of Louisiana and Florida, had his attention drawn to this subject. After examination, he concluded that they constituted a different species, which he named Sabal deeringiana, after his friend and patron Charles Deering (1852-1927), the founder of International Harvester. Samples sent back to the New York Botanical Garden from Small's 1925 trip are likely still stored there today.

| |

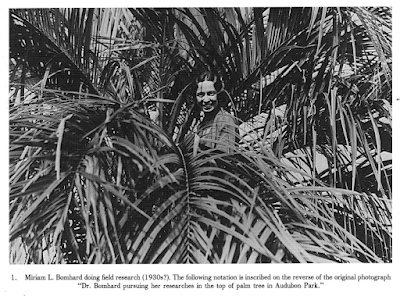

In the mid 1930s another Pennsylvanian, the botanist Miriam Bomhard, came to work at Tulane University in New Orleans. There she developed a specialization in palms. Field explorations in this area led her to discover many more examples of this strange Sabal. She expanded on the work of John Small by documenting numerous occurrences of the species across the Gulf Coast of Louisiana & Texas and by theorizing about its past distribution and future prospects.

The following internet comment represents, more-or-less, the contemporary view on this subject:

"Some people think there are different species or varieties of Sabal minor while others disagree. I have seen numerous Sabal minor plants throughout Louisiana that have developed a trunk, but there are many times more plants that don't develop a trunk. I don't think there is a Sabal louisiana or a Sabal minor var louisiana. Some of the variation depends on growing conditions and age. Areas that get flood regularly have older plants that have developed a trunk."

This observation on the controversy unfortunately misses the key point of contention. Sabal minor never, under any conditions, develops into an "arborescent" or tree-like stage; this is precisely why it is commonly called the dwarf palmetto. Sabal palmetto naturally grows tall unless it encounters a problem. Why, then, do some Sabal minor in Louisiana grow into a tree-like form? Small and Bomhard both knew this presented a problem.

Let's consult a description of Sabal minor given by a knowledgeable Baton Rouge-based palm enthusiast (emphasis added):

Sabal minor - Typically, not a tree but forms a short upright trunk under certain conditions. When this occurs it is most likely a var. known as Louisiana or a Brazoria hybrid. Traditional sources give trunk max. at 18' for Sabal minor in SE TX (any proof of this?). The tallest and largest are in Brazoria County (most likely primitive hybrids with S. palmetto) with reported hts. of over 20'. Either 23' or 27' and at the San Bernard NWR from what I hear is the largest. Unverified are reports of some at the Lance Rozier Unit of Big Thicket National Preserve said to be over 20', of uncertain classification. In Louisiana, the var. S. louisiana reaches a max. ht. of 13 ft (4 m) and trunks on old trees get up to about 7 feet tall. Excluding the E Texas hybrids, I'm not sure what the record would be for S. minor but it would probably not be much taller than the figures just quoted.

These two internet comments, both found on forums dedicated to palms, clearly demonstrate the issue which confounds even expert amateurs. The vast majority of Sabal minor are recognized as having no tree-like characteristics, but rarely this is observed. This writer understands

first-hand the taxonomic issue but follows the current scheme of

classification, leading the incongruence. In the illustration below, note the description: "It is a trunkless palm."

|

| From Palms and flowers of Florida (1940) by Francis Wyly |

|

| Here in the Centenary College arboretum, this patch shows characteristic Sabal minor growth pattern: low to the ground and spreading out. Horizontal, not vertical. |

|

| A straight and narrow trunk is evident on this growing Sabal palmetto. |

|

| Note the rounded and pear-shaped trunk, entirely different from that of the Sabal palmetto immediately above. |

|

| To adapt the words of Jeremy Bentham: if this a Sabal minor, it is "a Sabal minor on stilts." And Sabal minors don't have stilts. |

| |

| This composite photo demonstrates the concordance of Bromhard's Sabal louisiana (a specimen in what she describes as a "youthful climax" stage) with one in the arboretum. |

|

| As shown above, the developed trunk of Sabal palmetto is straight and regular. |

A mid 1990s retrospective on Miriam Bomhard's palm work describes how the confusion became the accepted standard.

"Bomhard was able to reactivate her study of native and introduced Louisiana palms. She gave a presentation on the morphology of the Louisiana palmetto (Sabal minor) at a scientific meeting held at her alma mater in December 1934 (1934). This was followed the next year with the description of a new species, Sabal louisiana (Darby) Bomhard, which recognized the arborescent form of S. minor as a distinct species, based upon original work by William Darby in 1816, J. K. Small n 1926, and supplemented with her own field work in 1933 (1935a). The new species was recognized by Dahlgren (1936). Over the following decade, on regular trips to Louisiana, Bomhard continued to collect field data on S. louisiana, which led to another publication on the subject (1943b). A year later, however, Batley (1944), apparently without knowledge of Bomhard's new publication, reduced S. louisiana to synonymy with S. minor. Glassman (1972) followed Bailey and considered S. louisiana a synonym and so it has remained."

From "Miriam L. Bomhard's Contributions to the Study of Palms" by Dennis V. Johnson, Principes, 40 (I), 1996, pp. 31-35.

This is the longest and most detailed post to appear on this blog; we hope that it contributes some insight into a long-running controversy. Thanks are due to the botanists of the past, along with Caroline Dormon and Dr. Leuck for providing these specimens.

You can find previous blogposts on these plants at the following links:

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2023/12/tree-of-week-sabal-palm-sabal-palmetto.html

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2021/02/louisiana-palmetto-sabal-minor.html

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2021/01/tree-of-week-sabal-palm-sabal-palmetto.html

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2019/05/tree-of-week-louisiana-palmetto-sabal.html

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2018/03/tree-of-week-sabal-palm-sabal-palmetto.html

https://centenaryarboretum.blogspot.com/2012/01/sabal-minor.html

See also:

https://archive.org/details/biostor-144959/mode/1up

Miriam L. Bomhard. Distribution and character of Sabal louisiana, Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences (volume. 33, no. 6; pages 170-182).